What did the second hand say to the hour hand?

See you again in a minute.

There are 86,400 seconds in a day. Why?

Such a strange number. Who thought of that? And why is it now universally adopted?

(OK, it might take slightly more than 60 seconds before you get fed up reading this page in its entirety, so just read the interesting bits.)

The clock on your office desk or your classroom wall is there to tease you. It mocks you, merrily ticking away, in its own time, when you want it to speed up a bit.

As you watch the clock, time seems to get slower and slower.

Despite what we think we see, we know that every second of the day lasts exactly the same period of time. There are 60 of them every minute, and 60 of those every hour. And in one day, there are 24 hours.

60 x 60 x 24. Why?

Well, we can trace the origin of these apparently arbitrary numbers back to ancient civilisations.

Around 3,500 years ago in Egypt, when twelve was considered a pretty important astrological number, they used the duodecimal (base-12) system for measuring, counting, designing gadgets, etc.

One such device was a T-shaped sundial, or rather sunbar, which had twelve notches, holes or pins that would indicate the current time.

Until that period, it was likely that people would use their bodies to tell the time. When they were hungry, it was time to eat. When they were sleepy it was time to sleep.

But to function efficiently as a society, a common time was clearly needed. Astrology seemed to work pretty well in those days so it was natural to use the duodecimal system to measure time periods.

Measuring time through the night was not so straightforward, but important nonetheless, particularly for night watchmen, bakers, those tending to livestock, etc.

Stars in the night sky were the answer, and they noticed that 12 particular stars neatly divided the heavens into equal parts.

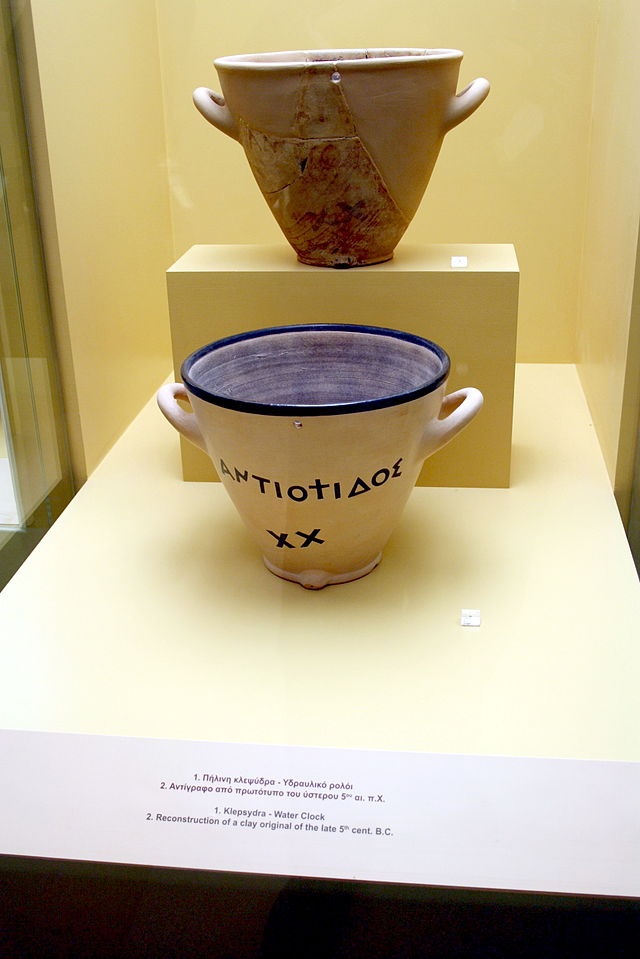

And when the night (or day) was cloudy, they topped up the bowl of the clepsydra, a water-powered timepiece that indicated the current hour. It never needed batteries but was a bit tricky to wear on the wrist.

Some historians believe the water clock was also used in China, as early as 4000 BC.

Yes, "Made in China" has been around for quite a while.

Thousands of years ago there probably wasn't much need for anything more precise than one hour, which is fortunate, because the actual length of each 1/12 day, and 1/12 night, varied throughout the year.

Indeed, until the invention of mechanical clocks in the Late Middle Ages, people were quite adept at coping with variable-length hours.

Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190-120 BC) proposed a neat system based on the 12 hours of daylight that equalled the time of the 12 hours of darkness that occur on the vernal and autumnal equinox days. But nobody apart from other mathematicians and astronomers were bothered too much.

Long before Hipparchus and other eggheads of the Hellenistic period, the Babylonians are believed to have used the base-60 number system called sexagesimal. Now the word "sexagesimal" might make schoolboys giggle a bit, but they soon realise later that the sexagesimal system rocks when it comes to dividing things into halves, thirds, quarters, etc.

The Greek astronomer Eratosthenes (c. 276-194 BC) used a sexagesimal system to divide a circle into 60 parts when drawing lines of latitude on a map (east⇔west). This was later enhanced by Hipparchus, who added lines of longitude lines (north⇕south). A couple of hundred years after that, the Greco-Egyptian Claudius Ptolemy refined the system by subdividing each segment into 60 parts, which were called "minutes". Each minute was further subdivided into 60 smaller parts, which were called "seconds".

But the water clocks and sundials continued to be calibrated in hours only.

Life seemed to speed up quite a bit during the Middle Ages and by the 16th century, we were ready for more precise timekeeping.

This happily coincided with the development of mechanical clocks, and it must have seemed obvious to subdivide hours on the circular dials just as maps were subdivided into 360 degrees. There was no time for clockmakers to agree on anything different, or to formulate anything better, than the system devised by earlier civilizations.

Since then we (well, not you and me, but a few clever folk) have refined the second to about nine billion energy transitions of a little caesium atom.

Don't worry if you don't understand what that means. Just make sure you haven't spent too much time reading this page when you should be getting on with more important things.