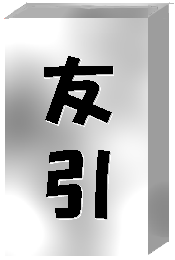

The Rokuyō meaning of those two kanji together is good luck all day, except at noon, with the idea that you may pull or involve a friend (or friends) into whatever you're doing.

Tomobiki used to have a slightly different meaning - whatever you were doing on that day would not end successfully. A bit like trying to assemble IKEA furniture without the manual. Therefore, it wasn’t considered a good day for winning at sports or games, since they’re best enjoyed with friends. After all, in the spirit of sportsmanship, a player wants their opponent to enjoy the game, even if that means letting them win. You could say Tomobiki is the patron saint of bad poker faces and suspiciously-generous chess players.

In the past, Tomobiki was called 'Tobiki' and originally used in competitions to mean a tied score, a stalemate or a mutually agreed draw - otherwise known as the ultimate way to keep everyone on speaking terms.

Nowadays, Tomobiki is a great day for weddings, as it’s believed to pull friends into the spirit of love.

But for funerals? Not so good. The idea is that the deceased might pull their friends to the 'other side' - and not in a friendly 'come sit with us' way. Traditionally, crematoria closed on Tomobiki due to a lack of funeral services, though this practice has become more relaxed over time.

If a funeral really must take place on a Tomobiki day, folklore suggests placing a doll in the coffin so that the doll, rather than a friend, gets dragged into the afterlife.

Of course, that's 100% codswallop. If a supernatural entity were powerful enough to pull someone into death, it should also be able to differentiate between a doll and a human corpse. That said, superstitions are rarely logical.

I've attended a Japanese funeral on a Tomobiki day and can confirm that the family didn't consider Rokuyō at all. No doll was placed in the coffin, and no supernatural shenanigans occurred. The funeral proceeded with decorum, and as with most deaths, the emotional weight of the moment left no room to consider superstitions.

There are a few other alleged consequences of Tomobiki:

During the Edo period, some samurai allegedly refused to go into battle on Tomobiki, fearing they might "pull" their comrades into death. On the flip side, some generals saw Tomobiki as the perfect day for a sneak attack, banking on their enemies hesitating due to superstition. If Sun Tzu were alive, he’d probably call this "psychological warfare by astrology".

I've seen no historical evidence to confirm these claims, but given how seriously many people took Rokuyō in the past, it’s not impossible that some warriors actually did consider it.

Most gambling is illegal in Japan, but back in the day, some gamblers believed Tomobiki was a golden opportunity to bet big - hoping that luck (and winnings) would be "pulled along" for their friends. Others avoided it, fearing their bad luck might spread, or worse, that they’d drag their friends into financial ruin. It’s the ancient equivalent of texting "Should I put my life savings on red?" and hoping your mate answers in time.

As mentioned above, I've no data comparing Rokuyō days and gambling success, but it's prudent to avoid gambling altogether, whatever the Rokuyō day is.

Some Japanese ghost stories claim that spirits or curses are more likely to "cling" to the living on Tomobiki. Because of this belief, exorcisms and spirit-banishing rituals were more common on Tomobiki days, especially in rural areas.

Some folks even avoided hospitals on Tomobiki, worried that sickness might "pull" them or their friends into extended illness. Of course, ignoring medical care due to superstition is about as smart as assuming horoscopes can diagnose your ailments. If you need a doctor, go, regardless of the Rokuyō day. (Unless the spirit of hypochondria is truly strong with you.)

Some couples avoid breaking up on Tomobiki, fearing their ex’s emotions might "cling" on, making it harder to move on. In contrast, matchmakers sometimes saw Tomobiki as a prime day to introduce people, hoping that the connection would stick.

But "breaking up" can be a gradual or sudden, so scheduling one around Rokuyō is not practical. For matchmaking, the most convenient day for both parties is probably more important than any superstition.

Traditional Kabuki and Noh theatre troupes sometimes avoided performing on Tomobiki if their play had tragic themes, lest misfortune in the story "pulls" itself onto the audience. Conversely, comedy performances thrived on Tomobiki, as laughter can be contagious. In other words, it’s a scientifically unproven reason, yet a spiritually endorsed reason, to go and watch stand-up comedy.

As with the samurai superstition mentioned above, there might be some truth about deciding whether or not to stage those performances - or it may be just one of many other weird and wonderful superstitions that actors follow. (See theatrical superstitions,)

I'm told that some social media users in Japan joke that posts made on Tomobiki "pull" engagement along, making it a good day for viral content. Some businesses even schedule PR campaigns on Tomobiki, hoping the news will gain traction and be "pulled along" to a wider audience.

So that's Tomobiki, which literally means "pull your friend".

Whether it’s luck, love, laughter, or just a really good meal - make sure you pull your friend into something nice today.