Daikokuten is one of the deities (fukunokami) of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan (Shichifukujin); the other six being:

Shiva is a principal deity of Hinduism and mentioned in the Buddhist texts as the fierce deity Mahākāla. In Japan, Mahākāla syncretized with the native Shinto god Ōkuninushi, from which he appeared as Japan's god Daikokuten.

Daikoku literally means "great blackness" and ten literally means "heaven"; in other words, the great blackness of heaven, a god to be feared. And yet in Japan, Daikokuten is believed to be a provider of prosperity. How can this be reconciled?

Images and statues of Mahākāla are often black, either through the choice of material, paint, or frequent coating with religious oil.

The English word "black" stems from the Proto-Indo-European bhleg-, meaning burn or scorch' The same root produced bleach, bright and white.

Without the dark colours, we wouldn't be able to see the white colours. The words on this webpage have a black-coloured font, which you are only able to read because they are displayed on a light-coloured background. The inverse is true, as you'll notice with the white icons at the top of this page, made visible by the indigo colour of the background.

It's a human reaction to fear the unknown, and since we cannot see anything when there's no light, it's a natural reaction to fear darkness. Therefore black is associated with evil, death, and generally things negative. This irrational reaction to black has contributed to racism against Black people.

Black magic and the black arts draw on malevolent powers. Nobody wants to be blackmailed or blacklisted for working on the black market. Black widow spiders are not so friendly. Yet a white feather is a symbol of cowardice and 'to whitewash' is to hide one's mistake. A 'white elephant' is something that's a waste of time, effort or money. And talking of money, if your account is in the black then that's pretty good.

In other words, the issue is not so black and white.

The Christian Bible's Old Testament often depicts Jehovah as a God of wrath against sin (with glimpses of His grace). This is complemented by the New Testament which shows the grace of God towards sinners (with glimpses of His wrath).

We see a similar description for Daikokuten's origin as Mahākāla, a fearsome god who feeds on people's flesh, but only of those who sin against the Three Jewels of Buddhism (Buddha, dharma and sangha). For Daikokuten, we have to assume there's less sinning against those Three Jewels, since his only job now is to bestow good fortune on his believers.

There's a legend that an 8th century Buddhist monk named Saicho, retreated to Mount Hiei, northeast of Kyoto, for an intensive study and practice of Buddhism.

Whilst there he encountered a hermit who introduced himself with words from the Lotus Sutra: "I remove the suffering of people and grant peace and the bliss of nirvana to this world." Saicho then asked, "Then please protect the livelihood of the mountain and the health of the monks who practice here, and ensure there is enough food to feed them."

The hermit promised, "I will provide food for three thousand people daily, and grant good fortune and long life to those who worship me." Saicho realized that the hermit must be Daikokuten. More monks joined him in the mountain and a monastic community developed.

Near the end of the 8th century, the capital of Japan moved to Kyoto. According to Chinese geomancy, the northerly direction from Kyoto was dangerous but the capital was believed to be protected from evil by the presence of Saicho's monastery named Enryaku-ji.

Saicho's prestige therefore grew, and with it the favourable reputation of the monastery which is now one of the most significant sacred places for Buddhism in Japan. Daikokuten is the patron of Enryaku-ji and today the monastery is easily visited using the Eizan cable-car.

The "good food, fortune and long life" promised by Daikokuten is still believed today. In particular, he is guardian for cooks and all kitchen workers. People who dream of financial riches tend to worship this god.

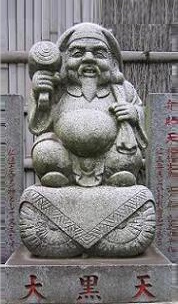

Daikokuten is usually depicted wearing medieval courtly hunting clothing with a hood or bonnet. He stands or sits on bulging rice bales and his portly belly implies he's well-fed and prosperous. In the sack slung over his left shoulder, he carries treasure. Exactly what type of treasure is unclear - perhaps it's the great treasure of wisdom and patience. In the old days, 'treasure' might have been sufficient rice to overcome hunger.

In his right hand he holds a lucky wooden mallet (uchide-no-kozuchi) that dispenses good fortune whenever he strikes it. The mallet often has the tomoe motif.

The three hyperbolic spirals (teardrops, commas, tadpoles, etc) chasing one another round a circle and believed to be based on magatamas found in Jomon-era burial chambers in Tohoku, Northeast Japan, and considered to be auspicious. The one on the right was shown to us by an expert in ancient Far Eastern artefacts. It is jade, from a site in Korea, dates from c. 350 AD, and carried in the pocket of this gentleman at all times as a lucky charm.

In Japan the tomoe is used as a kamon; a sort of heraldic coat of arms (ka = family, mon = crest). Like the cross in European heraldry, kamon were used especially in battle to identify individuals or members of a clan. They were first owned by the aristocracy and later rolled out to anyone associated with that community. Kamon are still used by Japanese, especially as decoration on formal kimono.