Japan has lots of gods, but the shichi (seven) fuku (luck) jin (beings) have been a popular cult of deities since the Edo period. Pictures and sculptures of these gods are seen all over Japan, either alone or as a group, and often on their treasure ship (takarabune).

Each lucky god (fukunokami) has a name:

Seven has been an auspicious number for thousands of years in countries around the world, and Japan is no exception. There are seven basic principles of the Samurai's philosophy (bushido), the Japanese Star Festival tanabata is on the seventh day of the seventh month, a baby's birth is celebrated when it's seven days old, a death is mourned for seven days, and again after seven weeks. In Buddhism, the main religion in Japan, people believe in seven reincarnations.

(More about the auspicious number 7 in Japan)

So it's not surprising that there are seven gods in the Shichifukujin.

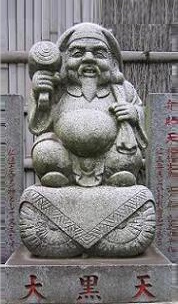

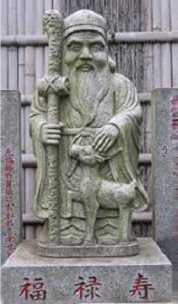

When you first see images of these seven gods, you might think they belong in a toy shop. Seven comical-looking characters, mostly with chubby faces, big grins and ridiculously large earlobes. Surely people don't worship these?

Yes, they do. Or at least they are treated with respect and honour to some degree.

Shichifukujin have been an important part of Japanese culture since the 15th century (Muromachi era). They come from different parts of Asia (mainly China, India and of course Japan) and from different religions (mainly Brahmanism, Buddhism, Daoism and Shintoism). Although most of these characters have a courtly or scholarly appearance, they were popularised by farmers, merchants and artisans. Consequently their treasures are perceived as immediately useful things such as rice, fish and cash, rather than gold or jewels.

Special focus is placed on these seven deities in the New Year. The gods are believed to arrive each New Year's eve on their treasure ship Takarabune to dispense gifts of happiness and luck to believers. Traditionally, before going to bed on New Year's Eve, children place a picture of the gods under their pillow to ensure a happy and prosperous New Year.

But this juvenile custom and the doll-like effigies are not just the domain of children. During the first seven days of the year, whole families visit temples and shrines to pay their respects to the Shichifukujin. Many of these places are dedicated to just one of the gods, so people often make a tour of seven shrines to see them all, to ensure they benefit from all types of luck.

This pilgrimage tour (Shichifukujin meguri) is not restricted to the New Year and usually takes place within the same neighbourhood. The tradition has been popular since the beginning of the Edo period (17th century). Today there are about twenty such groups of seven shrines in Tokyo alone and are over one hundred in Japan as a whole.

Separate from the Shichifukujin pilgrimage, is the traditional 'First Shrine Visit of the New Year' (hatsumode). At that time, millions of visitors pour into shrines around the country to pray for prosperity in the year ahead. Some shrines are considered more powerful than others and so become extremely busy with thousands of people, slowly trudging along the well-worn path leading up to the shrine to pay their respects.

And payment is made in the form of cash.

At the entrance of the shrine, there's a large wooden collection box for pilgrims to toss their coins into. Above the box is a huge bell, which people ring after depositing their coins, to alert the gods to pay attention to their prayers. After a couple of hand-claps, the pilgrim moves out of the way for the next person in line.

Although they visit Buddhist or Shinto altars, the pilgrimages aren't especially religious. Most Japanese have a relatively casual attitude toward their religious affiliations, and the New Year's visits are more of a chance to dress up, shop for lucky charms and socialize, than they are an opportunity to pray.

The Meiji-jingu shrine in Tokyo usually has the biggest crowd - over three million people each New Year. Instead of a collection box, there's a huge white sheet to catch the coins thrown by the crowd as they approach. Hard-hats are advised for the front row of pilgrims! Of course, the money you pay is an investment - the more you pay in, the more luck you will receive. Companies even send their senior managers with bundles of cash.

For some people, Shichifukujin epitomizes all the virtues of God, whereas for others this is a rather shallow view.

Where souvenir shops in Britain sell models of Tower Bridge and Big Ben, the US has the Statue of Liberty, Netherland clogs, Bolivia poncho, and so on, Japan is full of Shichifukujin.

Even the Christian celebration of Christmas made its mark on these Shichifukujin outside a resturant in Ito, Shizuoka Prefecture.

(Read more about Christmas in Japan on our sister website here.)

Yes, Shichifukujin are seen all over Japan; as stone statues, wood carvings, paintings, ice sculptures, and even acrylic stick-on fingernails (tsuketsume).

The set of fake talons in this photo were seen in a fashionable (Roppingi Hills) Tokyo 'nail art studio' window during the first seven days of January; the best time of year to see Shichifukujin in Japan.

Click image for details of each fukunokami.

Ebisuten |

Daikokuten |

Benzaiten |

Fukurokuju |

Hoteison |

Jurojin |

Bishamonten |