The Rokuyō we see today is from the early 19th century, but its birth is much, much older than that.

We don't know how much astrology and religion might have overlapped in the past, but today they are light years away from each other. (Read that as 'enlightened' years apart.)

If you're more familiar with Abrahamic than Eastern religions, just consider Genesis 1: 14 And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years

Even in Old Testament times it was known that the sun could be used to find the directions for north, south, east, west and anywhere in between, and the stars could do the same at night. The observed angle of the sun and position of the stars also indicated the seasons and together with moon phases gave us the basis for a calendar. So it's little wonder that in ancient times those cleverly helpful planets were revered as deities.

From scientific observation of celestial bodies (astronomy), star gazers could predict the amount of time before the season changed. In other words, the deities gave signs of what would happen in the future. Hence the birth of astrology.

In the New Testament Matthew 2 we read of the Magi ("Wise Men") who were experts in astrology. They followed Nativity Star which had heralded the birth of Jesus.

So astrology was firmly established long before western and eastern religions, and had great influence in shaping those religions. Even today in Christianity, astronomy is used to determine holy days the date of Easter - the first Sunday after the full Moon that occurs on or after the spring equinox.

But let's look at some Japanese history.

By the 8th century the lunar calendar was in use, and Shinto and Buddhism were well established. The history of the Japanese calendar is fascinating. Since 800 AD Japan has used a seven day week with names for the days corresponding directly with those used in Europe.

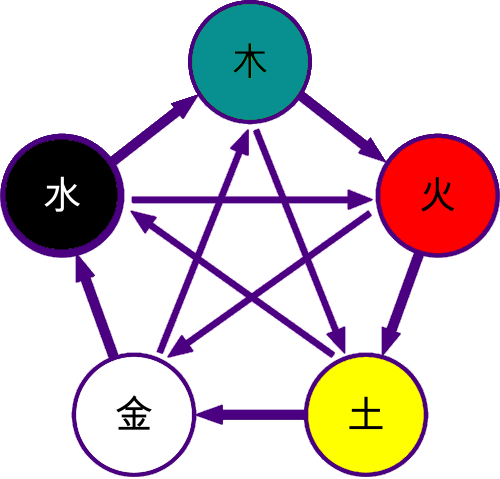

The seven day names were, and still are, from the two Yin & Yang of Chinese philosophy, plus the five classical Daoist elements: fire, water, wood, metal and earth.

| • Sunday - nichi-yōbi (yang - sun) |  Onmyō (Yin and Yang) (shade & light)  5 elements (Tue — Sat) |

| • Monday - getsu-yōbi (yin - moon) | |

| • Tuesday - ka-yōbi (fire) | |

| • Wednesday - sui-yōbi (water) | |

| • Thursday - moku-yōbi (wood) | |

| • Friday - kin-yōbi (metal/gold) | |

| • Saturday - doyōbi (earth) |

Although the seven days have been used in Japan for around 1,200 years, until the 19th century they also had a parallel six-day system, which had some effect on daily life.

The concept of Rokuyō (roku - six, yo - days) is believed to have originated in China. We don't know who engineered the system, though it's often attributed to Zhuge Liang (181-234), a Chinese statesman who lived through the end of the Eastern Han dynasty and the early- to mid-Three Kingdoms period. However, some scholars are doubtful that Rokuyō existed during that period.

Rokuyō was introduced to Japan from the end of the Kamakura period to the Muromachi period and began to be used in calendars from the end of the Edo period. The names, interpretations and sequence of the days have changed since then to its present form which has been accepted since the early nineteenth century.

Calendars are great tools for the government to control society; dictating festival dates and special days of observance, and the Rokuyō annotations were a personal benefit for commoners. To be told what day would be lucky or unlucky was a boon for gamblers.

There's been horse racing in Japan since the 8th century, originally as part of religious ceremonies for the Imperial Court. The sport progressed to major shrines and temples all over the country. To those who believed in omens and convinced by Rokuyō's fortune-telling, betting on horse racing was popular.

Gambling is greed and consequently strictly prohibited in Buddhism. Indeed, horse race betting was illegal in Japan until it was tacitly allowed between 1906 and 1908, and then established after horse racing legislation in 1923. Since that time, racing forecast papers have published the Rokuyō days, particularly for derby races.

As mentioned above, Rokuyō day names have changed over the years. During the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, today's Senshō was written as Sokuki, Sakimake was written as Kokichi and Butsumetsu was written as Kuubou.

It's understood that military commanders considered Sokuki during the Muromachi and through the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (Sengoku periods 1467-1615) to predict the outcome of a battle or war started on this Rokuyō day.

In the Kansei and Kyowa years of the mid-to-late Edo period, today's Senshō was written as Sokukichi, Sakimake was written as Shukichi and Butsumetsu was written as Koubou.

The name Rokki 六輝 ("six lights" or "six radiances") was originally an older name for the system, and sometimes still used. It emphasizes the astrological or celestial nature of the system — the idea that each day "shines" with a particular type of fortune or influence, evoking a more auspicious, celestial image.

This period continued to use the lunar calendar model, not only showing days of the month but advances in printing also increased the number of calendars with commercial advertisements.

The block print shown on the left carries an ad for a local merchant; a practice which continues today where customers are presented with their suppliers' calendar at the end of the year.

Today's advertisement calendars invariably include the Rokuyō notation for each day. (click image on the right to enlarge.)

And of course the calendar page on this website also shows Google ads.

Things changed radically in the Meiji era with major political, economic, and social changes which brought about the modernization and Westernization of the country. This included officially adopting the Gregorian calendar in 1873.

In the proclamation by the Grand Council of State No. 337 (1872) on 9 November comprised explanations and details of the change.

Specifically it included reference to Rokuyō: "Especially, most of the annotations on middle and lower part of calendars are absurd and largely prevent the development of human intelligence" and later proclaimed (24 November) "Now on issuing the solar calendar, the absurd annotations on middle and lower part of calendars will be totally forbidden including the lucky direction, unlucky direction, and the good or bad of the day, from 1873."

And yet for many years since, Rokuyō has been widely used in ordinary calendars, though usually not those made by public institutions such as the government. Even so, today Diet members have personal planners with Rokuyō notations for each day, and the Prime Ministers follow tradition and announce new cabinets on Taian.

Rokuyō is based on superstition of good and bad luck. Superstition only; not religious and has absolutely no scientific basis.

It no longer forms part of the official calendar in Japan, but it can still often be seen in small print on calendars and diaries.

Why? Well, probably to attract those interested in Rokuyō to buy the product.

Most people ignore it. Horse racing courses and pachinko parlours love it. Human rights groups have shown they hate it and have called of its abolition, saying that believing in superstitions such as Rokuyō leads to discrimination.

'Western' religions include the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, etc., which are distinct from 'Persian' and 'Eastern' religions of Buddhism, Confucianism, Hinduism, Jainism, Shamanism, Shinto, Sikhism, Daoism, etc.